The Uncommonly Applied, Common Factors

There seems to be a prevailing view that to be an accomplished psychotherapist one must be well versed in evidence-based treatments (EBT) or in those models that have been shown in randomized clinical trials (RCTs) to be efficacious for different “disorders.” The idea here is to make psychological interventions dummy-proof, where the people—the client and the therapist—are basically irrelevant (Duncan & Reese, 2012). Just plug in the diagnosis, do the prescribed treatment, and, voilà, cure or symptom amelioration occurs! This medical view of therapy is perhaps the most empirically vacuous aspect of EBTs because the treatment itself accounts for so little of outcome, while the client and the therapist—and their relationship—account for so much more. The fact of the matter is that psychotherapy is decidedly a relational, not a medical, endeavor (Duncan, 2014), one that is wholly dependent on the participants and the quality of their interpersonal connection. The client’s resources and resiliencies and the therapeutic alliance together represent the heart and soul of therapy.

A similar denigration of client and relationship factors is promulgated by those who promote the miraculous results of their chosen model—the model maniacs, replete with costly special training, supervision, and certification. They believe that their brand of therapy is the Truth with a capital T, representing how people actually are (e.g., there really are sub-personalities consisting of managers, exiles, firefighters, and the self according to the internal family systems model) as well as the path they must travel for change. To me, this is the ultimate phoniness, equating theories of psychotherapy with “truth”, rather than empirical/conceptual approximations of reality. Being genuine with clients may necessitate a humbling acceptance of the nondefinitive nature of psychotherapy theory and application, as well as the inherent complexity of human beings.

Model and technique offer only metaphorical explanations of how people can change, not edicts about how people must change.

A Little History

The common factors—what works in therapy—have a storied history that started with Rosenzweig’s (1936) classic article“Implicit Common Factors in Diverse Forms of Psychotherapy.” In addition to the original invocation of the dodo bird and seminal explication of the common factors of change, Rosenzweig also provided the best explanation for the common factors, still used today: namely, that given that all approaches achieve roughly similar results, there must be pan-theoretical factors accounting for the observed changes beyond the presumed differences among schools (Duncan, 2002b). Rosenzweig’s four-page article is still well worth the read, as is my interview of him (Duncan, 2002a)

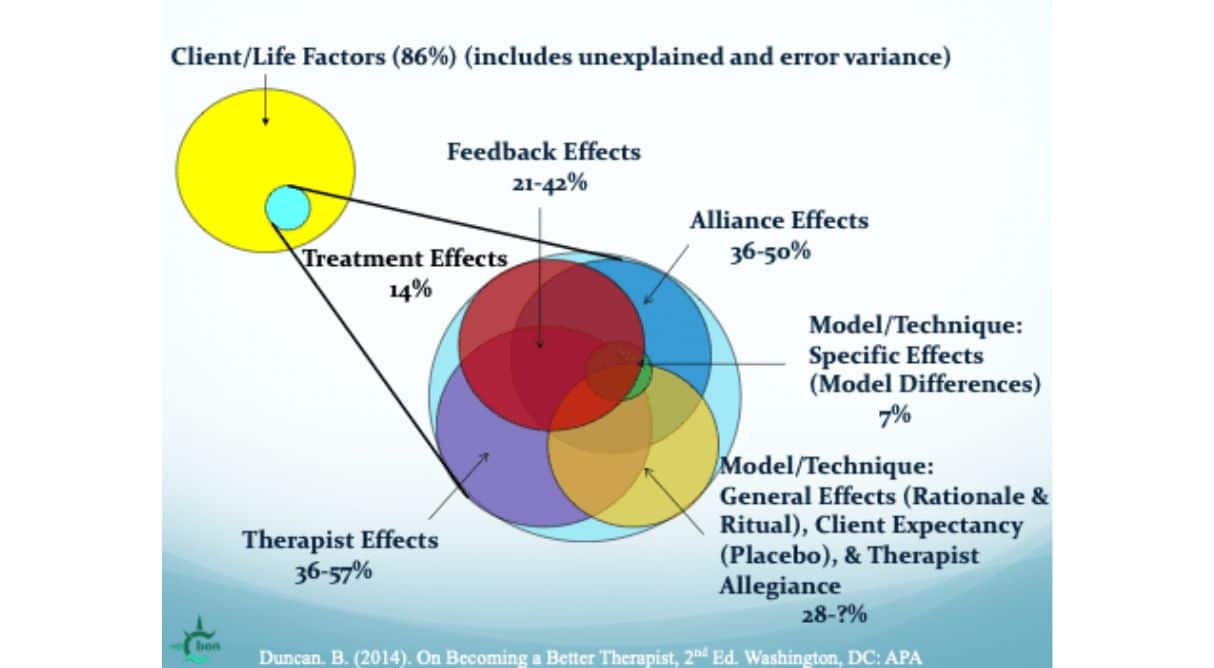

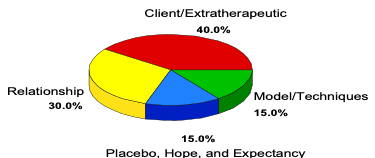

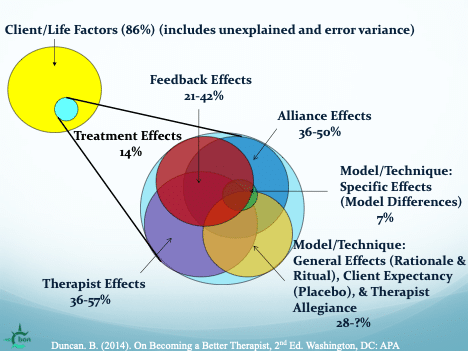

Inspired by Lambert’s classic pie chart delineation of the common factors (see above), my colleagues and I (Duncan & Moynihan, 1994; Duncan, Solovey, & Rusk, 1992) proposed a “client directed” approach to apply the common factors based on their differential impact on outcome. “Client directed” spoke to the influence of clients on outcome: their resources, strengths, and resiliencies, their view of the alliance, their ideas and theories of how they can be helped, and their hopes and expectations. The common factors, in other words, make the case that clients should direct the therapeutic process—their views should be the privileged ones in the room. Intervention success was described as dependent on rallying client resources and as a tangible expression of the quality of the alliance. I have been attempting to operationalize the factors ever since (Duncan, 2024).

The common factors help us take a step back and get a big-picture view of what really works, suggesting that we spend our time in therapy commensurate to each element’s differential impact on outcome.

To understand the common factors, it is first necessary to separate the variance due to psychotherapy from that attributed to client/life factors, those variables incidental to the treatment model, idiosyncratic to the specific client, and part of the client’s life circumstances that aid in recovery despite participation in therapy—everything about the client that has nothing to do with us. Calculated from the often reported 0.80 effect size of therapy, the proportion of outcome attributable to treatment (14%) is depicted by the small blue circle nested within the larger yellow circle at the lower right side of the left circle in the above figure of the common factors. The remaining variance is accounted for by client factors (86%), including unexplained and error variance, represented by the large yellow circle on the left. Even a casual inspection reveals the disproportionate influence of what the client brings to therapy.

My hallucinogenic figure also illustrates the second step in understanding the common factors. The second, larger circle in the center depicts the overlapping elements that form the 14% of variance attributable to treatment. The middle circle is a blown up version of the small blue circle. Visually, the relationship among the common factors, as opposed to a static pie-chart depicting discreet elements adding to a total of 100%, is more accurately represented with a Venn diagram, using overlapping circles to demonstrate mutual and interdependent action. The factors, in effect, act in concert and cannot be separated into disembodied parts. Download a Powerpoint version of my common factors diagram here.

Common factors research provides general guidance for enhancing those elements shown to be most influential to positive outcomes. The specifics, however, can only be derived from the client’s response to what we deliver—the client’s feedback regarding progress in therapy and the quality of the alliance. An inspection of my common factors figure shows that feedback overlaps and affects all the factors—it is the tie that binds them together—allowing the other common factors to be delivered one client at a time. Soliciting systematic feedback is a living, ongoing process that engages clients in the collaborative monitoring of outcome, heightens hope for improvement, fits client preferences, maximizes alliance quality and client participation, and is itself a core feature of therapeutic change.

Common Factors Notable Quotes and Comments

The Client, the Heart of Change

Until lions have their historians, tales of hunting will always glorify the hunter.

African Proverb

I hate to tell you, but we have been the hunters in the above proverb. I chose the word “heroic” for a previous book to highlight the client’s contribution to outcome as well as the field’s propensity to see the more “unheroic” sides of those we serve (see Duncan et al., 2004). I also, via literary device, wanted to expose psychotherapy’s hidden assumptions—the heroic psychotherapist, a knight in shining armor riding high on the white stallion of theory, brandishing a sword of evidence-based treatments, ready to rescue the helplessly disordered patient terrorized by the psychic dragon of mental illness. Hyperbole aside, the client’s role in change has been significantly dismissed, while the therapist’s part in change as the expert steeped in theory and technique has been greatly exaggerated. We do play a significant role in change, but we are not knights in shining armor. Using PCOMS allows clients to be the historians of their own change, central players of the psychotherapeutic process.

The Alliance, the Soul of Change

Listening creates a holy silence. When you listen generously to people, they can hear the truth in themselves, often for the first time. And when you listen deeply, you can know yourself in everyone.

Rachel Remen, Kitchen Table Wisdom

The therapeutic alliance consists of three interacting components: the relational bond and the degree of agreement between the therapist and client about the goals and tasks of therapy. The concept of validation, as a therapist response, embodies the relational bond as well as empathy, unconditional positive regard, and authenticity. Validation occurs when client’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are accepted, believed, and considered completely understandable given trying circumstances. Validation communicates that the client doesn’t have to worry about your perspective of them—you are planted firmly on their side and in their corner.

Agreement about tasks—finding a framework for therapy that both you and the client can believe in—is why it makes a lot of sense to ask clients about their ideas on how to proceed, or at the very least getting client approval of any intervention plan. Such a process has not been highly regarded in traditional psychotherapy—the search has been instead for interventions that promote change by validating the therapist’s favored theory. Serving the alliance requires taking a different angle—searching for ideas that promote change by validating the client’s view of what is helpful, the client’s theory of change (Duncan & Moynihan, 1994).

We can best explore the client’s theory by viewing ourselves as aliens from another planet. We seek a pristine understanding of a close encounter with the client’s unique interpretations and cultural experiences.

To learn clients’ theories and to privilege client perspectives, we must adopt their views on their terms, with a very strong bias in their favor.

Read more about the common factors and consider if the way you spend your time with clients aligns with the impact of these elements that run across all theories that create the context for change.